In 1989, a Turkish villager and his son were digging the ground on their property on the rocky hill near their village. Among the stones, which they removed, so that they may till and sow their plot of land, they found two strange, T-shaped ones. These stones had images carved onto their surface – some of which resembled animals.

The men loaded the stones onto their cart and hauled them to the local mosque. Upon seeing them the imam gathered the whole village, and began contemplating long and hard on what to do. Eventually, the imam decisively proclaimed: “These stones are incredibly valuable… but they do not belong to you, they belong to our entire people. You should take them to the museum in Urfa, and there they will surely give you a lot of money for them.”

The villagers did as they were bid and took the stones to the museum in Şanlıurfa (Шанлъурфа), a city with a population of roughly two million people, about fifteen kilometers from their village. However, things did not turn out like the imam had said, once they arrived at the museum. The expert who examined the stones was not impressed at all. He said that they were mere tombstones from the Byzantine period, of which there were thousands all over Turkey. He wondered whether or not he should take them, or send the villagers away and have the stones disposed of. In the end, he ended up taking them off their hands. However, he paid so little for them, that the villagers bowed their heads and were too ashamed to return to the mosque and tell of what had happened. They were angry that they had let themselves succumb to such fantasies, and more importantly – that they had tricked the entire village into fantasizing with them about the importance of these stones.

The expert didn’t even consider putting them up for display in the exhibit. He threw them in the museum yard and promptly forgot about them; at least after carefully describing the finds, who had brought them to him, and where they had come from.

Five years later, in 1994, Klaus Schmidt, an archaeologist at the University of Heidelberg, was – as he would do every other Saturday – strolling through the museum in Şanlıurfa (Шанлъурфа). Schmidt was the leading scholar in charge of all the various archaeological digs in the area for many years. He had made a habit of strolling around the museum, perhaps so that he could look upon his own finds in the the displays there, or to keep track of what had come in from the other sites, of which there were tens of in the region. Either that, or it was just his way of relaxing.

He was already on his way out, when he saw the two carved stones, tossed aside in the museum’s yard. He rushed back into the museum, screaming at the top of his lungs. Within minutes, all the experts and the administrators had gathered around him. It turned out that the museum had kept a very detailed account of how these stone s had been found and who had brought them in. Almost instantaneously, everyone there hopped into their jeeps, and within twenty-five minutes, along with the villagers they collected along the way, they arrived at Göbeklitepe. On only first inspection, Schmidt could already see other stones, which displayed signs of past human activity.

He would then go on to proclaim proudly, “Gentlemen, we have just discovered the cradle of civilization.” With the authority of one of the most respected archaeologists in the world, he ordered this place be put under guard, and on that very night, tens of policemen encircled the naked hillside.

It turns out Schmidt wasn’t the first to take notice of Göbeklitepe. In 1963, a Prof. Halet Çambel and a Prof. Robert John Braidwood examined the hill. Just on the basis of the surface-level finds, they had eyed it as a potential dig site. In 1980, Peter Benedict also toured the hill and wrote in an article, that something might turn up there. However, due to the abundance of other archaeological sites in the region, Göbeklitepe’s turn was yet to come up.

In 1995, Klaus Schmidt began excavating the site with a large team of archeologists, and in just the first couple of days it became apparent that this might be one of the most important archaeological sites in the world, capable of changing our fundamental understanding of human history.

What did Schmidt uncover under Göbeklitepe?

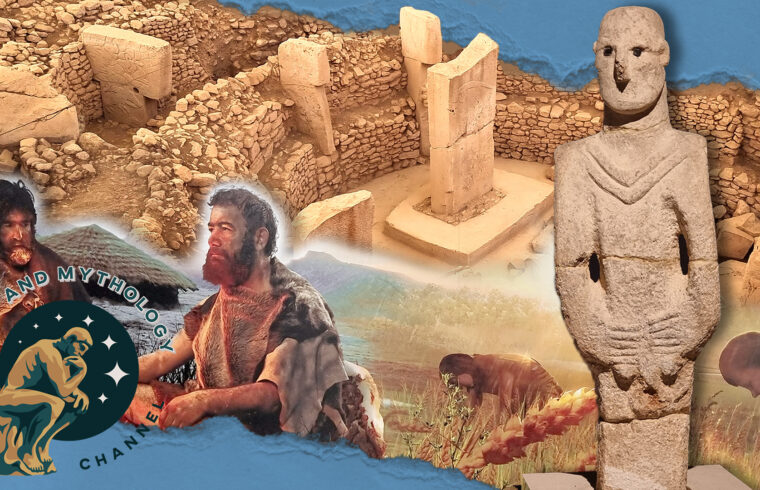

What has been uncovered so far, are four circles of stone walls, each with ten to twelve T-shaped columns embedded in them. The smaller columns can reach heights of up to three metres. The tallest two columns in each circle are placed in the middle, with the columns in Building D reaching heights of up to five and a half metres, and can weighing upwards of fifteen tonnes. Most of the columns are richly ornamented with carved reliefs, but we’ll talk more about those later.

The oldest circle, housed in Building A, dates back to around 9600 BC.

Even before beginning the excavation process, Schmidt scanned the hillside with specialised equipment. The final area totalled up to roughly the size of twenty football (soccer) fields.

The data shows that neighbouring the site are another sixteen circles, with at least another two hundred T-shaped columns. It’s believed that some of the structures are even older than the ones uncovered by the excavation, possibly upwards of two thousand years older.

Schmidt’s site only accounts for 5% of the area, where it is certain that finds can be uncovered. To this day, that percentage has not increased by much.

Unlike many of the archaeological sites round the world, Göbeklitepe has never been destroyed, or even damaged. It was buried by its creators – not once, but many times over. For a thousand years, people built these stone circles, covered them with dirt and soil, and built atop them newer, but smaller ones.

How old is Göbeklitepe?

Göbeklitepe is roughly 8900 years older than Homer, and at least 8100 years older than the events he describes in his works. 7000 years older than the oldest pyramid in Egypt, 6500 years older than Stonehenge, 5500 years older than the oldest known human civilisation – Sumer. And perhaps most impressively of all –older than the cultivation of wheat, and animal husbandry.

According to what history has taught us, a site such as this should simply not exist. At the time it is said to have been constructed, humans were yet to discover agriculture. Humanity would still have been at the stage of fractured groups of hunter-gatherers, thousands of years off from having organised enough communities to even be capable of constructing megalithic structures.

Yet, it exists.

What is Göbeklitepe, actually? Who built it? For what purpose?

As always, these questions have a variety of answers.

Let’s begin with the most improbable ones:

Aliens

Much like every large archaeological site, Göbeklitepe becomes grounds for theories that it was built by an extraterrestrial civilisation, or at least from a extinct race of giants who, through its construction, sought to send a message to future generations.

The first argument is the usual one for these kinds of theories – how one primitive hunter-gatherer community, who can’t even fathom the wheel, and are yet to develop pottery, are in possession of the kind of construction skills, necessary to take on a project, which would pose a challenge even today. How could they have moved fourteen tonne columns, carved them, stood them on end, and arranged them so carefully, before even having figured out how to make bread?

The followers of these kinds of theories seem to agree with the views of most scientists, including Klaus Schmidt, that the T-shaped columns are stylized statues of humans, only missing their heads.

The rest, everyone seems to have a different spin on. Some believe that their heads are missing, because they are depicting, not humans, but some other, alien race.

Astral Chart

According to a different theory, the site is an astral chart, a map of the skies, or even an astronomical observatory. Part of the depicted animals – spiders, snakes, and other geometrical elements can be interpreted as constellations. Followers of this theory believe that it was aliens who left us this map, others believe that it was some older, more developed civilisation, and there are even some who believe that the local neolithic inhabitants already had the knowledge on how to create such elaborate astral charts, making out amid the various paintings evidence of an extraterrestrial collision with a comet 9600 years ago – an event, which prompted the construction of said site, to mark the occasion.

Harbour for the Great Flood

In a different theory, Göbeklitepe was a harbour or shipyard, at which the ships, meant to safeguard humanity during the time of the Great Flood, were to be built.

The large T-shaped columns would act as posts to which new ships would be anchored and built atop. Followers of this theory rejects the idea that the site was buried by its creators, opting instead for what they see as the more likely scenario of silt and sediment build-up gradually forming after a series of floods. Once one of the levels was flooded, the ancients would build a new, higher level on top of it. The theory also proposes a new interpretation for the animal carvings, not as religious symbols, but seeing them as nothing more than ordinary signposts for what animal ought to go where.

The inhabitants of Göbeklitepe, much like Noah from the Bible, were at the ready to load not only people aboard their ships, but also their animals. The reliefs were to be used as indicators, for what kinds of animals to bring, and where to load them, so that it might be done easier and faster.

The Birth of Religion

Göbeklitepe is one of those rare cases, in which a scientific theory is far more radical and exciting than all the conspiracy theories spurred by the site.

If it were true, it would no doubt instigate such a colossal paradigm shift in our fundamental idea of history as we know it today, that it would change everything we might have been taught in school.

For a long time now, the commonly held belief was that civilizations appeared where there was a sufficient surplus of food available.

Hunter-gatherers were perpetually preoccupied looking for food, spending their whole lives working to procure it or crafting primitive tools, and fashioning simple clothing, to enable doing so even during the cold winter seasons.

It is said, that the revolution, which transformed these communities into civilizations, similar to our own, was the domestication of wheat. It is believed that about 10,000 years ago, several currently existing strains of grasses mutated, into what we nowadays refer to as rye, barley, and wheat.

The mutation itself, was incredibly small – a slight thickening of the bond that holds the grains to the stem, making it harder for them to fall off the ear. The result was disproportionately enormous. The ears became strong enough to let the grain ripen on the stem itself, rather than when falling to the ground. Perhaps more importantly, strong enough to be handled, harvested, and stored.

Of all the near-infinite varieties of plants which exist on Earth, very few produce enough protein to be worth growing and stockpiling. It’s practically just wheat, rice, and corn. It’s no wonder then that civilisation only develop where at least one of these crops can be found.

There are not many animals that can be domesticated. For example, in the entirety of South America, there is only one animal that can be domesticated – the llama.

About 10,000 years go, in an area called the Fertile Crescent, all the necessary conditions were met – the right crops, with the right mutation, in the right climate. Simultaneously, the region was inhabited by the right kind of animals for both food and labour.

According to our current understanding of history, this neolithic revolution, provided such a surplus of food, that part of the community could be freed of the need to look for food, giving birth to the crafts, art, religion, and what you’d generally call civilisation.

Göbeklitepe, however, might disprove this dogma.

According to Klaus Schmidt, there was never a permanent settlement at Göbeklitepe. He also refers to it as the first holy site in human history – a place where people would come and perform certain religious rituals.

During the excavations, huge quantities of animal bones were found. Perhaps the rituals involved large communal feasts. They would eat together and toss away the bones – none of which belonged to a domesticated animal species. All bones were from wild animals, predominantly wild goats and gazelles.

This would imply that the sanctuary was built and used before the advent of animal husbandry.

A small amount of grains have also been preserved. But, similarly, none of them are from a cultivated variety of wheat – only wild species.

This means that the religious complex at Göbeklitepe was in use before the communities of hunter-gatherers had transitioned into agriculture.

It is difficult to describe the significance of this discovery. It changes our fundamental understanding, not only of human history, but also our general preconception of how humans came to be.

Different schools of thought argue what came first – religion or agriculture. The Marxist and Positivist schools’ historical traditions believe that when enough food was stockpiled for there to be a surplus, all that newly freed up time, which would otherwise have been spent foraging and hunting, was now devoted to the pursuit of the arts and crafts. In a sense, humankind, eventually, almost out of boredom, invented religion.

This line of thinking implies that agriculture was discovered first, which then prompted people to establish settlements, where they then invented religion, built temples, and from there went on to build some of the first cities.

The existence of Göbeklitepe, however, asserts that religion was invented first. What’s more: Schmidt believes that it was precisely in order to support their religious needs, that the hunter-gatherers were forced to invent agriculture, the division of labour, and ultimately civilization.

How exactly did this happen?

Around the time of the last ice age, the hunter-gatherers were forced to follow the hordes of animals along on their migratory paths, in order to acquire food. 12,000 years ago, however, the climate began to warm up. Vast quantities of water would stream from the mountains of Anadola, down to the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. Entire new ecosystems of lakes and swamps would emerge, which attracted more animals. Hunter-gatherers no longer had to follow the herds around. The animals themselves would come to them, seeking these pools of water. One only needed to sit around them and wait.

This is how sedentism came to be.

All of this happened exactly around the time at which Göbeklitepe was constructed. Perhaps even slightly earlier, since some of the settlements in the area are likely to have appeared even earlier. After all, one of the first food stores was discovered in one of these small neolithic villages, within the greater region of Upper Mesopotamia, not too far from Göbeklitepe.

The presence of a food store means two things: First, that even before the domestication of wheat, there was enough food to leave a surplus. Sedentary living, as well as a surplus of food imply an increase in population. On one hand, a higher birth rate in communities, but on the other, the settlement of other clans, tribes, and groups in the are, with whom common rules for peaceful coexistence must be established.

The common ideas of what is good and what is evil, common rituals, common understanding of morality – that’s religion. There’s no better way to establish trust between the recently aquainted communities, than the construction of a temple, where you can lean on your neighbor, trust him, and ignore the fact that he is from another clan or tribe. All that matters is that he is of your religion.

But what kind of religion would that be?

According to Schmidt, the large T-shaped columns are stylized human figures, on some of which you can even make out hands.

Why don’t they have heads?

One of the statues in the museum of Şanlıurfa, vaguely of the same period, in which Göbeklitepe was constructed, shows that the local inhabitants were capable of creating faces with human likenesses.

Why then do the statues in Göbeklitepe not have faces?

Drawing from Göbeklitepe itself, including burials within the region from roughly the same epoch, help us understand.

The builders of Göbeklitepe buried their dead whole. However, after a certain period of time, they would exhume their bodies from their tombs, and separate the heads from the bodies. They would bring the skull, back to the home of their relatives, so that the dead might remain a part of the family. Headless, the body would remain in the afterlife.

Göbeklitepe’s four circles were probably seen as places where the barrier between our world and that of the great beyond was thin enough to facilitate inter-planar communication; and the T-shaped columns – the first gods. The hunter-gatherers would routinely share their food with them, as a form of ritual.

However, following the initial abundance of wild animals around the new water sources, their numbers would begin to dwindle. And religion would demand its regular tithe, in the form of vast quantities of food, to be eaten in the company of the gods. In order to satisfy their religious needs, people domesticated sheep, goats, cattle. At the same time, they cultivated wheat, and began engaging in agriculture.

According to some, precisely Göbeklitepe temple complex was the one that provided the ideological basis for the domestication of animals. The depictions of which, were placed below the level of the anthropomorphic god. This gave confidence to believers, that humans were the tamers of nature and the masters of animals.

This is an interesting theory, and has garnered many followers, but remains far from universally accepted. It is certain that Göbeklitepe is a sacred place, but the T-shaped columns as images of the gods? Can we even speak of a systematized religion that issues prescriptions for the daily lives of its followers?

We know for certain that Göbeklitepe isn’t the only sanctuary with T-shaped columns. More and more sites in the region are being uncovered, featuring the same kind of columns.

What do these T-shaped columns symbolise, with what religion were they associated, and which religion has inherited them today?

It is likely that the T-shaped column was a symbol of resurrection. The cross, on which Christ was crucified was–after all–T-shaped. In the early days of Christianity, it was exactly this T-shaped crucifix that was so revered. The shape we are more familiar with today appeared around the fourth century AD.

The point of origin for Christianity isn’t particularly far from Göbeklitepe, and it is very likely that a large subsection of the people living in the region today are descendants of the same hunter-gatherers who built it.

Christianity is far from the only religion to dabble in resurrection. The story of Lazarus, whom Christ brings back from the dead looks precisely like a vestige of of such a old religion, later woven into Christianity.

The Last Supper and the resulting Eucharist are suspiciously reminiscent of those communal meals, where the builders of Göbeklitepe ate the totem animals with their gods. It is very likely that Göbeklitepe was the cradle of many religions. Just fifteen kilometres from the temple in Urfa – the main settlement which seemed to be supplying Göbeklitepe with pilgrims. Urfa, later called Edessa, was also home to Abraham, the patriarch of the three great monotheistic religions, and one of the first cities to adopt Christianity.

Around 2-3 thousand years after the construction of Göbeklitepe, hunter-gatherers entered Europe through Anatolia. Some time later, from Upper Mesopotamia, they crossed whole the northern coast of Africa, entered Europe through Spain, and from there went to Britain, where they built Stonehenge. Another group went north, and mixed with the people who would later become the bearers of the Yamnaya culture, which would give birth to the future Indo-Europeans. The genes of the hunter-gatherers can be found found in all cultures that have developed mythology – e.g. in the ancient Greeks.

The End of Göbeklitepe

Göbeklitepe was not destroyed by a cataclysm, nor levelled by invaders. It was carefully buried by the people who worshipped there. Later, they would build a new, smaller temple atop it, which they would then bury again, and so on.

The need to do so remains the greatest mystery of the site – a question for which there is no definitive answer. The last time it was done was likely one thousand years after the construction of the initial temple, or at least the first to be uncovered, since it is assumed there are many more, even older temples buried beneath the hillside.

There exist two theories, which do not contradict each other, which also happen to be the most widespread. The first is that the temple at Göbeklitepe fell victim to its own success. Every small settlement in the vicinity probably wanted to erect its own temple, in which they could worship the gods from Göbeklitepe. Eventually, with the over-abundance of holy sites to chose from, there was no reason to visit Göbeklitepe anymore.

The second theory, is that the hunter-gatherers’ religion began to change, when they settled down and began to cultivate crops. Sensing that to old gods were dying out, they carefully and respectfully buried them, so that they would not be desecrated by people who did not understand them.

Mythology’s Long Memory

At the top of Göbeklitepe, grows a solitary tree. Since time immemorial, childless women from far and wide have come to sleep in its shade. Legend has it that everyone who has done so has then gone on to have children.

For centuries, Göbeklitepe was known exclusively via this belief. No one even suspected that megalithic structures laid just a few metres below. Nonetheless, everyone knew of the tree’s miraculous properties.

In the 1990s, when Klaus Schmidt began excavations, one of the first sites was around the sacred three. At its roots, they found a stone slab, with the depiction of a woman in labour. The slab was dated to around 8700 BC. Regardless of what religion may have practised in the area, the same story from 10,700 years ago, had passed down orally, and survived to this day.

Perhaps, even without suspecting it, we are telling one of the stories that 12,000 years ago hunter-gatherers told each other, sitting at a ritual table with their gods.